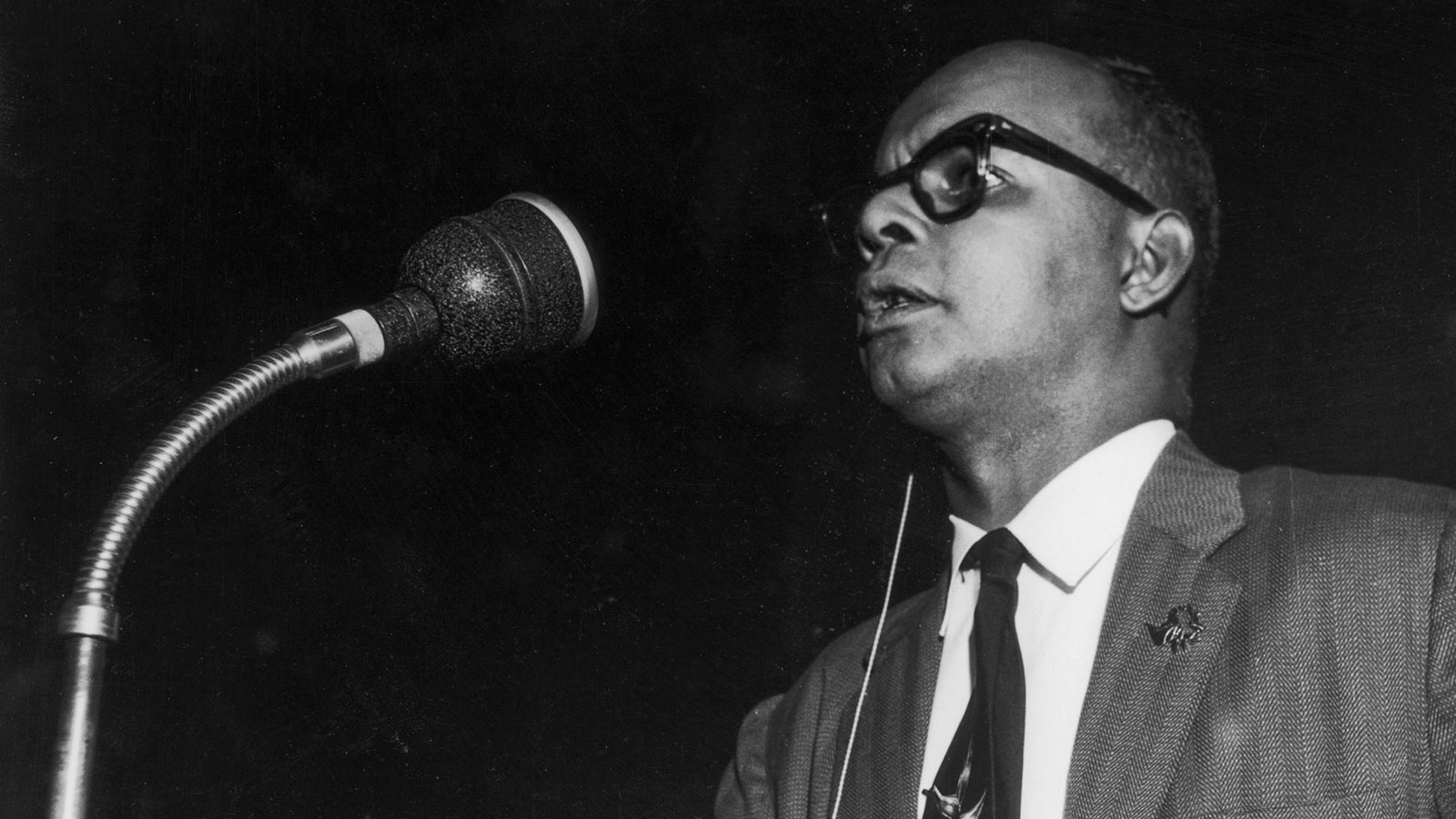

Eric Williams: The First Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago Through a Communist Lens

Eric Eustace Williams, the first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, is a towering figure in Caribbean history, celebrated as the "Father of the Nation" for leading the country to independence from Britain in 1962. A scholar, historian, and politician, Williams served as Prime Minister from 1962 until his death in 1981, steering Trinidad and Tobago through its formative years with the People’s National Movement (PNM), a party he founded in 1956. While Williams is often described as a pragmatic socialist, some interpretations of his policies, rhetoric, and intellectual influences suggest a flirtation with communist ideals. This article explores the case for viewing Eric Williams as a communist, drawing on his actions, writings, and historical context, while acknowledging the complexity of his political identity.

Early Influences and Intellectual Foundations

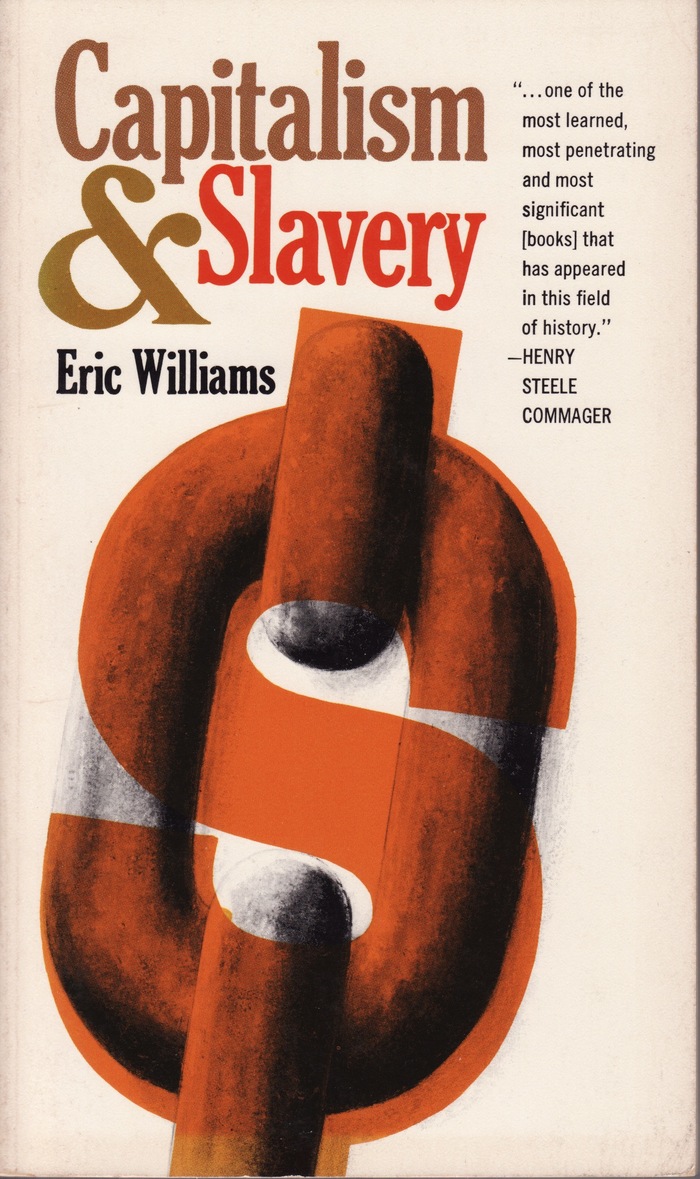

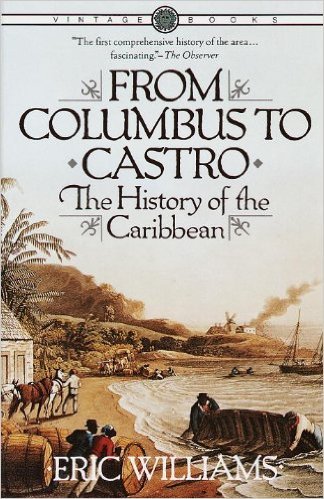

Williams’ academic journey provides a starting point for understanding potential communist leanings. Born on September 25, 1911, in Port of Spain, Trinidad, he excelled academically, earning a scholarship to Oxford University, where he completed his D.Phil. in 1938. His seminal work, Capitalism and Slavery (1944), challenged the economic underpinnings of British imperialism, arguing that the abolition of slavery was driven by economic necessity rather than moral awakening. This Marxist-inspired critique of capitalism—emphasizing class struggle and economic determinism—echoes communist ideology, even if Williams did not explicitly align himself with Marxism.

During his time in London, Williams mingled with prominent West Indian radicals like C.L.R. James and George Padmore, both of whom were avowed Marxists and Pan-Africanists. These encounters, detailed in his autobiography Inward Hunger: The Education of a Prime Minister (1969), likely shaped his anti-colonial worldview. His later tenure at Howard University in the United States from 1939 to 1955 further exposed him to leftist intellectual circles, where anti-imperialist and socialist ideas were prevalent.

Political Actions and Policies

Upon returning to Trinidad in the mid-1950s, Williams founded the PNM and launched a political career marked by policies that some interpret as communist in spirit. His approach, often labeled "pragmatic socialism," included state-led industrialization, free education, and social welfare programs—hallmarks of centralized planning akin to communist models. For instance, Williams abolished school fees and made education compulsory, a move that prioritized universal access over market-driven systems, reflecting a collectivist ethos.

His economic policies during the 1970s energy crisis further fuel this interpretation. Trinidad and Tobago’s oil and gas wealth was leveraged to fund national development, with the state playing a dominant role in resource management. The establishment of the first locally-owned commercial bank and the imposition of a 5% levy to address unemployment suggest a willingness to redistribute wealth, a key tenet of communism. Critics might argue these measures were pragmatic responses to colonial legacies rather than ideological commitments, but their alignment with state control over economic levers invites communist parallels.

Williams’ response to the 1970 Black Power movement also hints at a complex relationship with leftist ideals. Facing unrest from a movement influenced by Marxist rhetoric, he reshuffled his cabinet, removed perceived conservative elements, and sought to co-opt the movement’s demands for racial and economic equity. His proposed Public Order Bill, though withdrawn after opposition, aimed to curb dissent in a manner reminiscent of authoritarian communist regimes, suggesting a readiness to prioritize state stability over liberal freedoms.

Rhetoric and Public Persona

Williams’ public speeches, particularly those delivered at Woodford Square—dubbed the "University of Woodford Square"—blend scholarly analysis with populist fervor, a style reminiscent of communist leaders rallying the masses. His use of "picong," a calypso dialect, to critique colonial elites and champion the working class mirrors the revolutionary tone of Marxist agitators. In Inward Hunger, he recounts his commitment to educating Trinidad’s people about their history and rights, a mission that parallels communist efforts to raise class consciousness.

His international engagements also suggest a leftist tilt. As a founding member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and an advocate for West Indian unity, Williams resisted Western dominance, notably opposing a U.S. naval base at Chaguaramas in 1960. His strained relations with American interests and his inclusion in a 1965 delegation invited by British Prime Minister Harold Wilson to negotiate an end to the Vietnam War—a conflict steeped in Cold War ideological divides—position him as a figure sympathetic to anti-imperialist, if not explicitly communist, causes.

Counterarguments and Context

Despite these indicators, labeling Williams a communist oversimplifies his legacy. His "pragmatic socialism" was tempered by a cautious openness to foreign investment, particularly in the energy sector, which propelled Trinidad and Tobago to become the wealthiest Commonwealth Caribbean nation. This capitalist-friendly stance clashes with communism’s rejection of private enterprise. Moreover, the PNM avoided formal ties with trade unions or Marxist groups, and Williams himself never professed allegiance to communism, distinguishing him from contemporaries like Fidel Castro.

The Cold War context further complicates the narrative. As a small nation navigating superpower rivalries, Trinidad and Tobago under Williams maintained ties with the West while asserting independence, a balancing act inconsistent with rigid communist ideology. His death in office on March 29, 1981, left his ideological evolution incomplete, but his legacy leans more toward nationalist pragmatism than doctrinal communism.

Conclusion

Eric Williams was not a communist in the orthodox sense—no red flags flew over Port of Spain, and no manifestos called for the abolition of private property. Yet, his intellectual roots, policy choices, and anti-colonial fervor invite a communist reading. He was a product of his time: a Caribbean leader wielding state power to redress colonial inequities, drawing selectively from socialist and Marxist ideas without fully embracing them. Whether viewed as a pragmatic socialist or a crypto-communist, Williams’ transformative impact on Trinidad and Tobago remains undeniable.

.jpg)

.jpg)